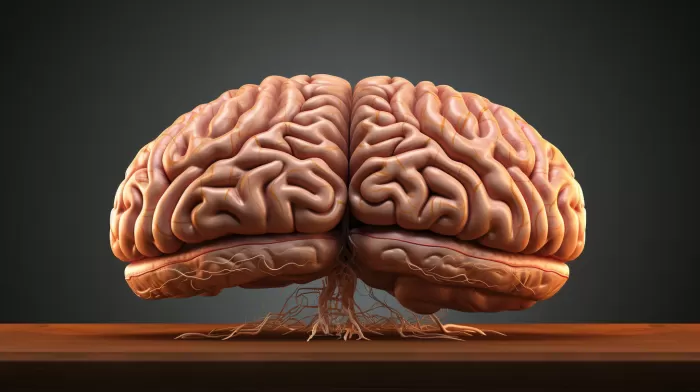

Put away the old stereotype of the muscle-bound person who exercises incessantly but can barely remember their own name. It’s time to embrace the notion that strenuous exercise not only grows bigger, stronger muscles, but it also probably results in a bigger, stronger brain. Research shows that physical activity can keep a person’s brain from suffering some of the side effects of aging.

The Wonders of Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor

Chances are you’ve never heard of a natural chemical called brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). But, if your brain hadn’t been working with this substance your whole life, you wouldn’t even be able to understand language. Your brain and nerves need a steady supply of BDNF to stay in good working order and keep your mental faculties functioning reliably.

Researchers have found that exercise boosts BDNF particularly in the hippocampus, a learning and memory center in the brain that forms a curved, elongated ridge inside your skull. The neurons in the hippocampus depend on BDNF for their production and protection.

In lab studies, scientists discovered that animals bred to be as active as marathon runners have significantly higher levels of BDNF than animals who lead sedentary lifestyles. “When you exercise, it’s been shown you release BDNF. BDNF helps support and strengthen synapses in the brain. We find that exercise increases these good things,” says Justin Rhodes, Ph.D., a researcher at the Department of Behavioral Neuroscience at Oregon Health & Science University’s School of Medicine. So, by boosting BDNF activity, experts maintain, you may be able to promote the health of your brain.

Improving Memory with Exercise

A growing number of studies show that when exercise increases BDNF, it produces measurable effects on learning and memory. In one experiment, scientists had college students take tests that measured cognitive performance before and after light or strenuous exercise on stationary bicycles. They found that both levels of exercise boosted BDNF levels (measured in blood tests) and improved exam scores in students.

Another study, this one on 144 pilots over the age of 40, examined the relationship of BDNF to performance in the cockpit. The researchers had the pilots use flight simulators over the course of two years in order to observe how their abilities changed in relation to their ages and levels of BDNF. The scientists found that all of the pilots in the study performed somewhat worse in the flight simulator testing as they aged. However, the ones who had a genetic susceptibility to less BDNF activity in their brains lost a good deal more skill over time than did others who had more BDNF. As the researchers noted, if certain individuals produce less BDNF (due to their genetic inheritance), this lack “…could predict the rate of decline in skilled task performance in middle-aged and older (otherwise) healthy individuals.”

But fear not, even if your DNA dictates that your body may not produce super amounts of BDNF, experts believe exercise can help save your brain. In an interview with The New York Times, researcher Dr. Ahmad Salehi, an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford, said that “exercise is probably even more important” for people whose bodies don’t make much BDNF. “But for everyone, the evidence is very, very strong that physical activity will increase BDNF levels and improve cognitive health.”

BDNF and Appetite Control

The benefits of BDNF don’t seem to stop at the neck. Further lab research shows that BDNF may help keep pounds off your middle. Studies at the Sackler School of Graduate Biomedical Sciences at Tufts University School of Medicine show that BDNF seems to be necessary for you to feel full after you eat. When BDNF levels slip, the brain apparently has more trouble knowing when you’ve eaten enough.

While this effect hasn’t been definitively shown in people, Maribel Rios, Ph.D., one of the researchers who has worked on animals, notes that individuals who have the genetic tendency to produce less BDNF also tend to be more overweight. “This is bound to be an important area of obesity research as more than a quarter of the American population has been estimated to carry mutations in the BDNF gene,” she says.

If you’re still pondering the question, “To exercise or not to exercise?” don’t let couch potato inertia stop you from at least walking around the block. That simple movement may help protect you from the thousand natural shocks that the brain is heir to. So, the next time you’re contemplating whether to stay home or head to the gym, remember that exercise is not only crucial for physical wellbeing, but also mental health and cognitive function.